(An excerpt from my book Died in Long Beach - Cemetery Tales)

Seeking HealthMany who find obituaries of loved ones who died in Long Beach often wonder why they came to Long Beach in the first place. A number of the obits list the person only having been in town a short while before they found their eternal resting place in either Long Beach Municipal Cemetery or Sunnyside Cemetery. Many of us living now, take the medical marvels that science has discovered within the last fifty years for granted. However, back at the turn of the 20th century you were considered "old" if you lived to be 50 years of age. Diseases that we now have inoculations for were prevalent then. Smallpox, infantile paralysis and tuberculosis were common medical problems. Often there was nothing doctors could do and the only hope was prayer. However, science was advancing. Physicians discovered that patients with tuberculosis improved if they moved to a dry climate. Sea air and a regulated diet were also considered valuable in combating the disease. Long Beach had the sea air and a relatively mild climate year round. It was the perfect place to build a sanitarium.

Long Beach Sanitarium

A pretty flowered walk led the way to the Long Beach Sanitarium at Tenth and Linden. The $60,000 sanitarium, which was also known as the Long Beach Hospital, opened in June 1906. Though it wasn't quite finished, patients flocked to its doors. All were impressed. There was a great electric fan in the basement, run by an electric motor. It took only three minutes to change the temperature in a room by the mere push of a button. The hospital was on the list of "must see" stops for tourists. Several times a day tour companies brought visitors to view the marvels the sanitarium offered. They gawked at the treatment rooms, where clients took invigorating baths and received massage therapies, and were amazed at the static room where electricity was used in treatments. Many families lived at the sanitarium for months at a time while one, or several, members regained their health. To accommodate the religious education of the young, there was a Sunday school and various devotional exercises practiced throughout the day. During evenings residents were treated to lectures, such as "The Evil Effects of Stimulants and Narcotics."

A pretty flowered walk led the way to the Long Beach Sanitarium at Tenth and Linden. The $60,000 sanitarium, which was also known as the Long Beach Hospital, opened in June 1906. Though it wasn't quite finished, patients flocked to its doors. All were impressed. There was a great electric fan in the basement, run by an electric motor. It took only three minutes to change the temperature in a room by the mere push of a button. The hospital was on the list of "must see" stops for tourists. Several times a day tour companies brought visitors to view the marvels the sanitarium offered. They gawked at the treatment rooms, where clients took invigorating baths and received massage therapies, and were amazed at the static room where electricity was used in treatments. Many families lived at the sanitarium for months at a time while one, or several, members regained their health. To accommodate the religious education of the young, there was a Sunday school and various devotional exercises practiced throughout the day. During evenings residents were treated to lectures, such as "The Evil Effects of Stimulants and Narcotics."The Long Beach Sanitarium used the "Battle Creek" idea, practiced by John H. Kellogg. At his Michigan sanitarium, Kellogg advocated total abstinence from alcoholic beverages, tea, coffee, chocolate, tobacco, and condiments. He preached a meat free diet and believed milk, cheese, eggs, and refined sugars should be used sparingly, if at all. Man's natural foods, Kellogg claimed, were nuts, fruits, legumes and whole grains.

There were about a hundred stockholders in the association running the sanitarium, among them twenty-two local physicians. There was no resident physician, each patient called in his or her own doctor.

Dr. W. Harriman Jones, whose Harriman Jones Medical Group continues to this day, was one of the driving forces behind this new sanitarium and later became one of the most prominent physicians in Long Beach. Born in Battle Creek, Michigan, February 22, 1876, Jones came to California when he was three. He attended Cooper Medical College, now Stanford University School of Medicine, and received his medical degree in 1899. Dr. Jones started his practice in Long Beach in 1902 and became the city's first health officer, instituting sewers, garbage collection and sanitary inspections. In 1930 he opened his own clinic---the Harriman Jones Clinic on Cherry and Broadway in Long Beach. On June 17, 1956, he died in the hospital that had once been the Long Beach Sanitarium---St. Mary's Hospital.

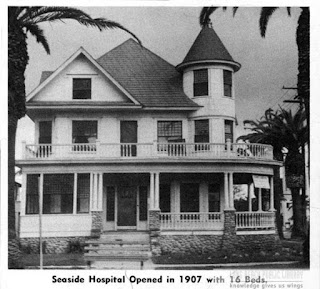

Shortly after the Long Beach Sanitarium opened in 1906, local physicians decided it was time for a real hospital. Dr. Jones had used a small house at 327 Daisy as a hospital, but something larger was needed. Area doctors first considered the old Porterfield home at 519 Cedar, but when neighbors protested they were forced to look elsewhere. In 1908 they rented the H.L. Enloe home at Broadway and Junipero for $60 a month. Each physician contributed $200 and elected Dr. Lewis A. Perce chairman of the board. Perce's wife suggested the name Seaside Hospital and Perce donated a sign with the hospital's name. By 1912, the doctors' needs had outgrown the capacity of the house. A new hospital was needed.

The new facility at 1401 Chestnut was something to be proud of. Sitting atop Magnolia Hill, on Fourteenth Street, the hospital had polished hardwood floors made sound proof by cork covering. Rooms of restful brown tints, each equipped with an electric call button nurses had to come into the room to turn off, greeted patients. Front rooms on the second floor had private baths and doors large enough to roll beds out upon the broad balcony on nice days. There were four private wards able to accommodate sixteen patients, and a maternity ward for 40 new mothers. An operating, dining room and morgue (accessible from the driveway, but discreetly out of sight) were outfitted with state of the art equipment such as huge electric fans, gas ranges and an elevator. In 1935 the original 16-bed hospital was increased to 275 beds and in 1960 Seaside Hospital became the Memorial Hospital we know today.

The new facility at 1401 Chestnut was something to be proud of. Sitting atop Magnolia Hill, on Fourteenth Street, the hospital had polished hardwood floors made sound proof by cork covering. Rooms of restful brown tints, each equipped with an electric call button nurses had to come into the room to turn off, greeted patients. Front rooms on the second floor had private baths and doors large enough to roll beds out upon the broad balcony on nice days. There were four private wards able to accommodate sixteen patients, and a maternity ward for 40 new mothers. An operating, dining room and morgue (accessible from the driveway, but discreetly out of sight) were outfitted with state of the art equipment such as huge electric fans, gas ranges and an elevator. In 1935 the original 16-bed hospital was increased to 275 beds and in 1960 Seaside Hospital became the Memorial Hospital we know today.