|

| Dr. M.A. Schutz |

I was surprised to come across an urban

legend in writing this blog. According

to a 2002 Mayfair High graduate, the story about orphans helping autos

climb Signal Hill was already well established by the time she entered

school. She told me she heard that your

climb up the Hill will be easier if you put baby powder on your tires. It seems the abused orphans from the Signal

Hill home will help with the ascent---the proof being the tiny footprints left

behind in the baby powder! The story she heard was that they had been abused, and they felt helping a car up the steep incline would speed up their rescue.

It is intriguing to trace down legends, most

of which have some base in fact. Here’s

what I found.

SIGNAL HILL’S ORPHANS’ HOME

In 1904 segregation was the norm, but a dream of universal brotherhood could be found in a home atop Signal Hill. It was hoped it would be a place where all could live in peace

regardless of nationality or religion.

For years

Dr. Michael Alexander Schutz and his wife had the dream of creating an

orphanage for children of all nationalities.

In 1904 the couple purchased four acres on the area of Signal Hill known

as Crescent Heights to build their visionary home for orphans and

castaways. The doctor’s idea was to give

them not only a home but an education to prepare them to someday enter the

working world and be self-supporting.

The July 24, 1904 Los Angeles Herald described their vision in which they would rear

children of all nationalities in an atmosphere of love. The children would be

taught trades, and when they reached the age of 14 they would be given the

option of going out into the world or staying with the family.

This is

a labor of love, declared Dr. Schutz. Life wouldn't be worth living to me if I

couldn't do something tangible and practicable for the world. If we could make

it so that all could live in peace with one another, and each should help his

neighbor, life would be far happier than it is today. The world today is

man-made. God made no distinctions between his children. We were meant to dwell

together, and that will be the purpose of the institution which we are

founding. We shall teach no religion other than the fatherhood of God and the

brotherhood of men. Adults are not prepared for such a step. Humanity has been

struggling, from the beginning and each man is looking after his own wants and

forgetting those of his neighbor. With babies it is different. We will take

them when they are far too young and tender to have formed any ideas, and it

will be an easy matter to instill into their lives feelings of love and

fellowship. They will be taught that they are all the children of one God, and

there will be no distinctions made between black, white and yellow.

The Russian born Schutz,

received his medical training in Bellevue Hospital, New York, and was for four

years connected with the Dansville, New York, sanitarium. He and his first wife, Hulda (1857-1900)

moved to Long Beach in 1894 and started their own sanitarium and a hotel they

called the Riviera. Now with his second

wife, Pearl, (who had spent 5 years working for the Salvation Army in New

York), he planned on building a two-story house on Signal Hill large enough to

accommodate a dozen children as well as their own two children, Helene Emeth and

Murray Ahura.

Their income would be

largely supported by Schutz running the Schutz Sanitarium, and the Riviera

Hotel, at 325-327 W. Second Street in downtown Long Beach. Schutz hoped that by planting mulberry trees

on his Signal Hill property he would have a second source of income, supported

in part by silk worm and silk manufacturing.

In

October 1904, the couple secured their first baby for their International Home

for Children, a one-year-old Korean boy, Asha.

The boy’s father, who came to America to study law and medicine, could

not care for the infant when his wife became sick. He thought the Schutz’s home

the best solution to his dilemma.

In July 1908, Schutz visited

a Los Angeles organization which dealt in finding homes for young infants. Schutz wanted to take custody of two 5-month

old babies, one black, one white, but was turned down on the grounds that since

his “establishment” was not a church institution the children could not be

placed there. Dr. Schutz was upset. He not been given a face-to-face interview

with the organization, the decision was based on hearsay. If he had been

granted a hearing he would have explained his principles of universal brotherhood

and how in his orphanage there was a Korean, a Filipino and American children.

They ate at one table, slept in the same room and received their schooling at

home from a private teacher.

|

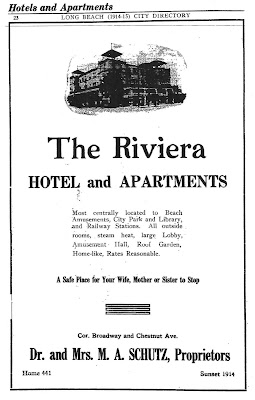

| Riviera Hotel |

In April 1909, the Schutzes adopted a 5 month

old Yaqui Indian baby boy, Raymond Eawahta Polomares, who was found by

missionaries in an Indian battlefield in Mexico where the child’s father had

been killed. The child’s mother Mabyla,

only 15, was also adopted by the Schutzes.

By October of that same year the Schutzes had Japanese, Korean, Indian,

Mexican, Portuguese, Australian, Fiji islanders and Americans as part of their

international family. Schutz had turned over the running of the sanitarium and Riviera

Hotel to Doctor Edward Bailey so Schutz could devote his time to his orphanage. But

the sanitarium, along with its hotel, apartments and treatment rooms ran into

financial difficulties, partially due to Long Beach’s anti-alcohol stance. By

1911 Schutz was back to being both proprietor and physician at the Riviera

Apartments, Riviera Hotel and what was now called the Riviera Treatment Rooms.

In 1913 he moved the sanitarium to Elsinore, but still managed the Riviera

Hotel and Apartments until 1918 when he sold them to A.T. Tibbits.

What did Schutz believe in other than

universal brotherhood? Besides stressing a vegetarian diet, and hoping some of

his charges would intermarry and create a new race of unbiased racially diverse

people, it seemed he had an interest in spiritualism. Spiritualism was in vogue during the early

part of the 20th century, and in August 1910, Schutz became the moving force

behind creating a Spiritualist temple in Long Beach. The plans showed an

elaborate structure resembling an Egyptian temple which would cost about

$20,000. A location tentatively considered was a lot just east of the Riviera Hotel

at Second Street and Chestnut Avenue. Schutz didn’t get a church built where he

wanted it but in 1912 a much less costly and not so elaborate Spiritualist

abode, the First Spiritualist Temple, opened at 327 W. Second. It moved to 415

Linden in 1913, later changing its name to Universal Temple.

LONG BEACH’S FIRST SANITARIUM

Many came to

Long Beach for their health, many suffering from “consumption” better known

today as tuberculosis. Physicians discovered that patients with tuberculosis

improved if they moved to a dry climate.

Sea air and a regulated diet were also considered valuable in combating

the disease. Long Beach had the sea air

and a relatively mild climate year round.

It was the perfect place to build a sanitarium (also spelled sanatorium,

or sanitorium), which Dr. Schutz did in 1894. An article in the July 7, 1894 Los Angeles Herald describes Schutz’s sanitarium in Long Beach:

The

medical sanitarium of Long Beach, Cal., established for the successful

treatment of chronic, nervous and female diseases. The most modern and best

equipped sanitarium in Southern California. Highest of references. For any

further information address Dr. or Mrs. M.A. Schutz, proprietors sanitarium,

Long Beach, Cal.”

The sanitarium was successful, and in

March 1896 the idea of building a larger sanitarium was contemplated. The March 1, 1896 Los Angeles Herald reported:

The

proposition of building a large sanitarium by a syndicate, urged by the

proprietor of the one in present use, Dr. M.A. Schutz, has met with

considerable favor among some of our most enterprising local capitalists, who

are quick to see the advantages of the enterprise as a means of investment and

will gladly put their money in it. There is no doubt whatever that if a large,

well-appointed sanitarium building were now here it would be the best means of

advertising the innumerable advantages Long Beach possess over all the other seaside

cities as a health resort. As it is, the fame of the sanitarium now presided

over by Dr. and Mrs. Schutz has reached very far with five Wisconsin women

coming Tuesday for treatment.

In July 1896 articles of

incorporation were filed by Dr. Schutz for the Long Beach Sanitarium Company.

The purposes of the corporation were to carry on a medical and surgical sanitarium,

establish a school of hygiene for nurses, issuing diplomas to graduates. It

seemed Schutz needed additional capital to achieve these goals. The capital

stock of the corporation was fixed at $20,000, divided into 400 shares.

Directors were: Dr. M.A. Schutz, Hulda A.V. Schutz, Dr. O.C. Welbourn, P.E.

Hatch and F.E. Ingham, all of Long Beach.

In March 1897, Schutz opened the

sanitarium doors to celebrate the forty-ninth anniversary of modern

Spiritualism. In the afternoon a baptism was held for infant Bryan Snow. The Los Angeles Herald (3/31/1897) reported the

platform was surrounded by lovely decorations of vines and flowers, but the

ceremony was different from that in vogue in more orthodox churches. The child,

instead of being sprinkled with water, was strewed over with flowers. White

symbolized purity; red, life and energy, and yellow, the intellect.

In 1900 Schutz decided to add a

hotel to his Long Beach holdings, but he needed investors. The Long Beach Hotel

and Sanitarium Company was incorporated in April 1900, with a capital stock of

$25,000, divided into 500 shares, of which amount $9,350 was subscribed. The

directors were: M. A. Schutz, M.D.; H. G. Brainerd. M. D.; J. W. Wood, M.D.;

F. L. Spaulding, Will H. Townsend, Harry Barndollar, P. E. Hatch, R.R. Dunbar,

H.F. Starbrick, all residents of Los Angeles or Long Beach. In February 1905 Dr.

Schutz bought out the other investors. He planned to make extensive

improvements to the hotel and put in an elevator and convert the basement into offices.

In February 1910

Schutz was offered $50,000 for the Riviera Hotel property. He refused to

consider the deal, believing the property would only increase in value (Los Angeles Herald 2/20/1910). Long Beach was growing. On Saturday, June 24,

1911, the Port of Long Beach opened for business. Lumber yards and a mill had already been

established near the harbor to prepare for the big business expected to come. Schutz

and many others believed this and other signs of progress meant tremendous

growth and progress for Long Beach.

The 61-year-old Schutz died December 29,

1924, at the Convalescent Hospital, 2089 E. Broadway after a week’s

illness. His 74-year-old son Murray was

interviewed by Bob Sanders of the Press

Telegram (10/19/1976) but said nothing about the orphans his family helped

raise. Instead he talked about his

father and the Riviera Hotel, the information somewhat different from that

presented in earlier sources:

My

father started practicing in Pasadena in 1896. It seems he graduated in 1894,

1895 or 1896 from the University of Southern California medical school and went

directly to Pasadena. Around that time

he ran out of patients during the summer months because he was told everybody

goes east in the summer. A German friend

recommended going to Long Beach where there was a Methodist campground that

attracted 7000 people. My father did just that and in 1900 bought a section of

land where, with the help of financing, he built the Riviera Hotel. My father

also bought 4 acres of land on Signal Hill, and I remember picking blackberries

for a penny a box for a farmer nearby.

Murray remembered the hotel advertised “One

Hundred Rooms Elegantly furnished: All Outside rooms, many with Private

Baths.” Regardless of the number of

rooms, the hotel’s days were numbered.

In 1918, according to Murray, five days after the United States entered

World War I, the mortgage on the hotel came due and all financing was

frozen. To meet the payment his father

had to sell the 4 acres of land on Signal Hill in 1919 just two years before

oil was discovered there. If he hadn’t

sold he would have made a fortune.

ORPHANS DISAPPEAR

What happened to the orphans? The 1920 U.S. Census showed M.A. Schutz,

Pearl, Helene and Murray living at Elsinore in Riverside County. What had happened to all the other children? The

1910 census had listed 7 children living with Dr. and Mrs. Schutz: there were

their own children, Murray age 7 and Helene 8; Korean born Asha, age 6; Alp, 7;

Tate, 5; Earwatha, 1; and Mabyla Polomares,

16. Where were the other children in

1920?

What of the urban legend claim that Schutz

abused his orphans? The only proof I’ve

been able to come up with appeared in the October 16, 1913 Los Angeles Times: “After Marshal’s Scalp: Sanatorium manager

charges officer with spreading slanderous stories. Action Deferred.”

By the time the article appeared Schutz had

moved his sanatorium from Long Beach to Elsinore. Elsinore had attracted

visitors since the 1880s because of the mineral springs near the lake. After 1893

the lake’s level sank almost continuously for about 10 years, which is probably

why Schutz chose Long Beach originally for his sanatorium instead of Elsinore.

But by 1903 the lake level began to rise, and by 1913 Schutz became owner and

manager of the Elsinore Sanatorium, but kept the Riviera Hotel in Long Beach.

The Times

reported that Schutz made a formal complaint against Elsinore City Marshal

Haworth, charging him with conduct unbecoming an officer. Schutz accused Haworth

of circulating slanderous stories about him and with interfering with how he

raised his children. Haworth claimed that Schutz had no right to punish them. Several

Long Beach people, including the Chief of Police and a police detective, were

present at the hearing and testified as to the good reputation of Dr. Schutz in

Long Beach. The matter was finally

settled when Haworth publicly apologized to Dr. Schutz before the Elsinore

Board of Trustees and a highly interested audience.

So what about the urban legend? Perhaps this 1913 article relating to

corporal punishment of the orphans, plus Schutz’s belief in Spiritualism, led

to the story of the ghostly children reaching out from beyond the grave to help

drivers in their climb up the Hill---and the driver perhaps rescuing the orphans

from Dr. Schutz and his abusive ways. Or perhaps the orphans were just practicing kindness and "universal brotherhood," principles they had learned from Schutz, in helping drivers in the steep assent up Hill Street.

I’ve been trying to find out what happened to

the orphans. Perhaps they were sent to

another group interested in Schutz’s ideal of universal brotherhood. In 1904

the Los Angeles Times reported that

the Schutzes were assisted by many philanthropic citizens. Chief among them was

the Thimble Club of the Rathbone Sisters, who were not only financially

interested, but expected to take an active part in the care of the little ones

“and in the work so unselfishly undertaken by the doctor and his wife.” (LA Times 6/5/1904). A search through

genealogical data bases revealed nothing about the orphans. According to the

1910 U.S. Census, all shared the surname Schutz, with the exception of Mabyla

Polomares. I did find that daughter Helene became a doctor and died in New York

in 1937, she never married. Son Murray was involved in the stock market in the 1920s;

he died in Berkeley in 1982. Wife Pearl Kelly Schutz died in 1949 and is buried

at Forest Lawn, Glendale.

Perhaps some readers will remember the orphans and

what became of them or have more to add to the urban myth? If so, please share.